I found this essay on a back-up disk in Sefton’s office. He wrote this in 1998.

Our family is defined by its origins in grimy, beautiful South Wales. On one side the wild flair-rich valley Morrises, on the other, the conforming, performing urban Davieses, and I have suffered the schizophrenic pull of two cultures and two psyches.

The Morrises are represented by Mama, for she was born Edith Maud Morris at the Railway Hotel, Treorchy, in the Rhondda Valley to David Morris and Margaret Ann Morris (née Salathiel) in 1895 – her birth certificate says on June 28 but celebrated throughout her 63 years on June 18, so who cares!

In an early sepia, crumbling, family photograph she sits with my great-grandfather, John Salathiel, moustachioed and tieless in a dark suit, for all the world like some prairie tycoon, his (first ?) wife, drab grey and shapeless.

We do not know if she is his first wife, because dark rumours whisper around his Rhondda house that he married an American woman when working in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania but found he didn’t like her, so returned to Wales without her and married my great-grandmother. Since, in my childhood, he was married to Bopa Mary, who is not in the photograph, who knows how many spouses the upright, God-fearing John Salathiel wed?

To his right sits his daughter, my grandmother, known to us all as Mam, who looks proudly, arrogantly, confidently beautiful in a long dress with tailored skirt and elegantly patterned top set off with a white ruff. Mama sits, a sad-looking child in white dress and with ringlets and fringe, and even then seemingly myopic. Sad-looking with justification if I have accurately remembered the stories of childhood I absorbed on her knee and, later, during long winter evening chats while Dada attended cabinet meetings at the Liberal club.

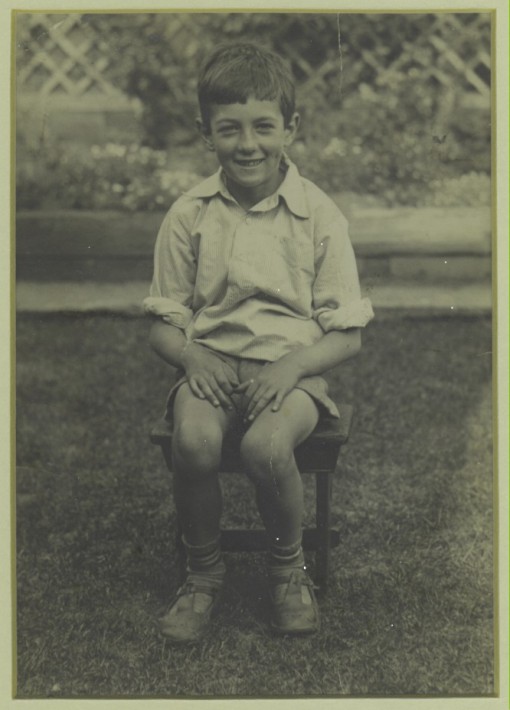

Morris Family Group

Tales of a loving, swift tempered father and conceited, indifferent mother, for Mam was ever infatuated with self and unable to show affection or love to her children or grandchildren. When Mama was nine, Mam had the operation on her knee which rendered her a bandy-legged limper, an affliction crippling to lesser mortals, but renounced by Mam as a detraction from her self-gratifying beauty but no cause to change her active life. The cause ? Who knows? Adults do, but to us children it lies firmly under the family carpet where brushed long ago, but strongly suggestive of intemperate frolics after closing time at the Railway Hotel.

But where was David Morris when the family was photographed? My grandfather died before I was born, but I know him well. Handsome in single-breasted button-up suit complete with white tie and red rose button-hole, he stands in wedding photograph behind his beautiful satin-gowned sixteen-year-old bride, left hand on cane-handle, right hand on bowler hat, a handsome, moustachied and youthful blade worthy of such a catch. While his young bride ran the Railway Hotel, he hewed coal under the lumbering hills of the Rhondda until he also entered the brighter, beery world of hotels and pubs as an itinerant manager throughout South Wales, providing Mama with a rich treasure-chest of tales and anecdotes and “personalities”.

Like Davy John, four-feet nothing, who, when the local tailor quotes a low price for a suit like grandpa’s, because it contained less cloth, said “Duw! Duw! How dare you – I’ll pay the same as Davy Morris!” Or of her maternal grandfather waking from a snooze in the bar only to find someone had shaved off half his beard while he was asleep. Grandpa was a typical Morris – gentle, loving father who played a heavenly violin to Mama’s piano accompaniment, but capable when angered at mistakes, of smashing his bow across the keyboard. Alas! it seems his temper did him little good, for, when only 48, he returned to his native Llandybie to lie in its rural churchyard.

Mama led a transhumant life across South Wales – the Railway, the Bunch of Grapes, the Ivybush, and others, with little schooling but an education in life, until, nine years old, she just about abandoned school to look after Mam, who by now had produced three more children and was crippled. The baby sister, Gwenny, died young from scarlet fever, but Mama, Margaret and Rachel formed a triumvirate of fun-seeking, style-conscious energy focussed on flitting and skipping upwards, out of the poverty and mundanity of their proletarian, coal-dusted environment.

Nothing was impossible with laughter, effort and will – a belief they all three took with them to their graves. Mama, while detesting her name, remained Edith Maud, but Margaret became Peggy and Rachel became Rita. Peggy knew no bounds to her devices for character metamorphosis, emerging eventually from her chrysalis a beautiful and vivacious brunette; a pseudo-sophisticated, cheating, frivolous gal-about-town in metropolitan Swansea, where she married uncle Billy Cowden, a ship’s captain turned dock-pilot and curry-cooking recluse, until he fell from a ship’s ladder and was forced to retire. He must have been a strong man, for he survived marriage to Peggy for many years, until this burden, together with bad health and financial and other worries, drove him in his car to Langland cliffs and over the edge – “Oh! but he chose such a lovely spot to do it”.

Undeterred, after a suitably expensive Mediterranean sea-cruise, from whose rarified social atmosphere she never fully recovered, Peggy devoted her widowhood to moulding her two daughters into unprincipled gadflies, a task in which she failed with once-married, loyal, gentle, handsome Pamela, but succeeded with thrice-married, ravishingly beautiful, vivacious and eventually alcoholic, Vivienne, who stands forever shamed for having dropped me on, and broken, my nose when I was a baby.

They spoke posh and lived in a classy house in classy Uplands – “we don’t have mice in our neighbourhood, Edith!” – which we occasionally visited for lectures in stylish living from our humble, mice-vulnerable home in Harle Street. When poverty and German bombs forced an evacuation, Peggy took the Morris escape-route to the Plough Inn in rural Carmarthenshire where she successfully married off Vivienne to a dashing and well-heeled army major, who died happy from a Japanese bullet before he could suffer years of marital bliss with Vivienne – the first of three similarly blessed husbands who expensively paid the price of worshipping her beauty. Once it became safe again, Aunty Peggy returned to Swansea, until her tastes outstripped her income, when she sought retirement in the arms of a comfortable widower who had not too long to live.

Aunty Rita equally craved stardom but remained earth-bound as the loving, embittered wife of Uncle Reg, the debonair first-world war airforce veteran whose flights of fancy crash- landed into the small outfitting shop in Newport where he worked as an immaculately clad, underpaid assistant. No posh house from those wages! So another Morris takes to the commercial road – to the Three Salmons Inn in semi-rural Monmouthshire where, by dint of energy and waspish badinage with her clientele, she creates an affluent, swanky, upper-middle class inn from a run-down working-class pub, much to the annoyance of the local working-class.

Here she reigns supreme – and unhappy, because Uncle Reg “can’t do it, you know!” and her abundant, useless maternalism festers into nagging, critical domination of Uncle Reg. who smiles and says, “Yes, dear” to every new humiliation, and calmly competes with her in polishing up a sterile, disinfectant house that never became a home. But I loved Uncle Reg. because he could draw aeroplanes and tanks and animals, and I loved Auntie Rita because she laughed and mimicked and danced, and because she loved Mama more than anyone else except Eric and me.

Mama somehow got employment in Lloyd’s Bank – quite an achievement for someone who virtually left school aged nine, but the Morrises never let strict adherence to the truth inhibit their ambitions, and when asked at her interview if she had her School Certificate, she readily affirmed, bearing a mental image of the paper she was given to say that she could leave school early to care for her invalid mother. Thereafter intelligence and guile allowed her to learn from those around her and to graduate to a position behind the counter of the Neath branch from which she was able to attract a husband in the shape of William Ivor Davies, post-office clerk.

Just as the Morrises represented sparkling irresponsibility, so the Davies family were ikons of look-over-your shoulder respectability and reliable dullness. Morris flame dancing from the coal they hewed from Rhondda hills, Davies probity hardening the steel they smelted and rolled in the tinplate works of Melincryddan, in Neath.

How I hated the stale-apple smelling gaslit gloom of the London Road terrace house where lived Grandpa and Grandma Davies with their daughter, sweaty-fat Aunty Gladys and her husband, Uncle Tom. Grandpa was a small trembling man who died from an accident at the works when I was young, but Grandma sat spreading in immobile self-satisfaction by the suffering fire, too fat to move by herself and waited on being waited on by her sycophantic daughter.

I never saw her leave her high-backed wooden chair and wonder now how she performed the most basic human functions, because there was no bathroom in the house and the only lav. was down the yard. I presume she somehow reached her bed but I couldn’t be sure of it; perhaps she had always been in that chair, through marriage and childbirth and sickness. She was certainly in it the day she died.

They had not always lived in London Road, of course, because Dada was born on September 4th. 1892 in Helen’s Road, Melincryddan, Neath, a mean street in the poorer part of town, leading to the canal and the tinplate works where Grandpa worked. Here he lived with his parents and, eventually, his two brothers and sister, all younger than himself, but, unlike Mama, his childhood was not retold to me, yet I sensed the poverty and the conformity which shaped his carefulness with money and social relationships – don’t do anything different because you’ll be laughed at, like Grandma laughs at Mama’s stylish clothes – “who do she think she is, any’ow?”; look after your pennies, which don’t grow on trees, and save, save, save, so that you can enjoy counting them in your straitened old age, as you sit in your unheated house eating your meagre diet.

Win a place at Neath Grammar School, only to leave aged fourteen to work with Mr. Beddoe, the plumber, to save the family from even direr poverty. Improve yourself by getting a job in the Post Office, where you will sort mail for the rest of your working life, to support your brothers Ewart and Harry, who extract teeth and smug self-satisfaction from the success your efforts provide for them. Return from serving King and Country as a wireless operator in France to your humdrum job in the sorting office in Neath. But then you meet Mama, and life begins for Eric and me at 29 Harle Street, Neath.

And so, my script for the great drama of life is written in genes fighting a war between the happy-go-lucky, be-different, don’t-give-a-damn Morris cohorts and the Davies be-careful, get-a-good-pension, what’ll-the-neighbours-think brigades. What an inheritance!!